There is an excellent description of the types of Cornea transplants on the NHS website which can be viewed here

The remainder of this page was written in 2009 but is still contains useful information.

When to go for a transplant

Corneal transplants have been refined to an exceptionally high level of expertise over the years, and KC is one of the most commonly encountered indications. For other conditions, the surgeon is usually dealing with a seriously unhealthy cornea which may be opaque and vascularised. In such cases, there is much to gain and nothing to lose from the standpoint of achieving a visual improvement, but there is a high risk of rejection and transplant failure from other complications.

|

| Figure 1. Early 1970’s ‘vintage’ transplant. Note the kink at the inferior host / donor junction. This gave rise to astigmatism over 20.00D, but the transplant has survived over 30 years |

The keratoconic cornea is thin and distended, but otherwise essentially healthy, at least from a metabolic point of view, and avascular. For this reason, there is a far greater probability of a successful outcome with a keratoconus indicated transplant than anything else. However, for the same reason that the cornea is healthy and crucially, clear, there remains a possibility of a reasonably good optical correction with a contact lens of some kind.

Corneal transparency and scarring in keratoconus

The normal high level of corneal transparency is because of the uniquely regular stromal fibres. The cornea often becomes less clear as KC progresses, but the process is more dystrophic than inflammatory. The fibres have a tendency to break up leading to sub epithelial scarring, but is not usually associated with vascularisation. Therefore, even if the corneal scarring becomes quite advanced, the chances of a successful transplant are still much higher than other indications.

There is no convincing evidence that scarring in KC is associated with contact lens wear. Sometimes there is hardly any after a lifetime of contact lens wear, sometimes it happens so rapidly that there is no useful vision even when there has been little or even no contact lens wear. There may be some superficial erosion of the epithelium, but this would have to be long and protracted, and would reach intolerable levels of discomfort, before causing any lasting damage. There is very little to gain by trying to predict how quickly such changes are likely to occur. By the same score, there is no evidence to support the claim that contact lenses retard the progress of KC.

|

| Figure 2. The same eye as seen in Figure 1 fitted with a corneal RGP lens. The acuity was as good, but it was not an easy one to fit with a corneal: the lens was very mobile and the edge of the lens is seen resting on the lid margin. |

That is not to say there are no complications with contact lens wear. It is possible that, if severe, they could cause potential surgical problems, should it be necessary to proceed with a transplant. However, in general, while the problems of contact lens wear never completely go away, actual lasting serious complications of contact lens are relatively unusual.

Defining transplant success, failure and survival

There is a very complex debate around the definition of corneal transplant outcome. I was once picked up by one of the consultants on that point when giving a presentation, when referring to success at a discussion group, the reply came …. ‘you mean survival ‘ , …. and I would go along with that.

If the donor cornea is clear, it has survived, if it is not clear, it has not survived. But even this is not that straightforward. You can take 100 corneas and say number 1 is totally opaque, while number 100 is perfectly transparent. The 98 corneas between the two form a continuum of increasing transparency. At any point on this scale, two corneas would be adjacent on the transparency scale, one a miniscule amount more transparent than the other, but for all intents and purposes inseparable. So where exactly the distinction is made between survival and non survival is another matter for debate.

What percentage of transplants survive?

The known outcome for most management options in any medical field is generally expressed in terms of the situation at five years post operative or post initiation of treatment. The fact is that it is not easy to collect conclusive information: people move, and some do not attend follow up, so prognosis for a longer period becomes increasingly less reliable. A fair and honest answer for keratoconus indicated transplants is that 95% to 96% are seen to survive five years. This is emphatically not to say that they fail after five years, but the information upon which that information is collated is less accurate.

The Australian Graft Registry (AGR) has been producing good data for many years. Their best estimate is for ten year survival has been shown to be 90% to 92%. However, I am aware of one person included in that group who underwent a repeat transplant in the UK within ten years, so there is at least one incorrectly recorded case for which the final outcome was not known to the AGR. Extrapolation from this suggests a reduction of 5% to 8% survival for every five years. The survival rate for repeat transplants reduces for each subsequent attempt, so the second one would have perhaps a 90% to 95% chance of survival; the third perhaps 80% to 90%. Much depends on the state of the cornea at the time of the repeat transplant. if clear but with an intolerable and unmanageable astigmatism, or if cloudy but avascular, the chances are still good.

I know some centres state a higher survival rate, and I am also aware that many transplants have lasted much longer than ten years. In fact, some people regularly attending our clinics have transplants which were carried out in the early 1960’s and still going strong. That is over 40 years in some cases, but this kind of anecdotal data does not stand up to statistical scrutiny. I am aware of those cases because they are wearing scleral lenses to correct high refractive errors or astigmatism post transplant. In my opinion, these are stunningly successful surgical results carried out under difficult circumstances, and the fact that scleral lens wear is necessary for good vision does not detract from that at all.

What level of vision?

|

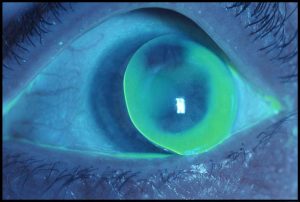

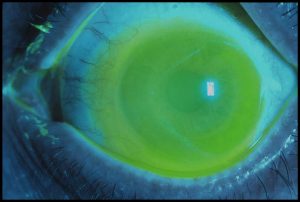

| Figure 3. The same eye illustrated in Figure 1 fitted with a scleral lens giving full fluid coverage, illustrated with a fluorescein picture, fully correcting the astigmatism with an acuity of 6/9. |

The principal reason for a transplant must be that irrespective of the best possible contact lens option, the vision is not up to day to day requirements. So what is a suitable level of vision? Failing to meet the legal driving requirement is the only commonplace yardstick that springs to mind. However, while driving is important, other people can be chauffeur, or bus driver, if a person has a level of vision which is satisfactory for everything else. Inability to carry out designated responsibilities once having arrived at one’s place of work is quite a different matter.

It may be that a contact lens is required to achieve the best vision, prompting the question ……. ‘If I still need to wear lenses post op, what is the point?’ ……. This is not valid because, given a healthy, surviving transplant, a significant improvement in best contact lens corrected vision would be expected post op. Also, visual performance is measured according to the ability to distinguish high contrast letters on a chart. It is not easy to assess vision in other ways. Distortions and ghost images in a more normal visual environment are not easily quantified but are massive problems to some people with KC. They would probably be reduced dramatically post transplant. On the other hand, while the best corrected pre-op vision with contact lenses may be declining, a reasonable result without a surgical intervention may be perceived as preferable. A transplant has the potential to be life changing, contact lens management maintains the status quo.

Was it successful?

|

| Figure 4. A more recent attempt, still somewhat protrusive in profile, but without the junction irregularities so often seen with transplants in earlier times. |

An assessment of survival is simple and straightforward compared to analysing success. About 50% of post transplanted corneas need a contact lens for the best visual result, and it is certainly no easier than pre-op KC. Post transplant comprises our second most populous group of scleral lens wearers: somewhere between a sixth and a fifth of our scleral lens wearers, totalling not far off 300. KC sufferers who are fed up to the back teeth with contact lenses may not agree that still needing sclerals or any other contact lens after surgery constitutes a successful outcome.

On the other hand, there is usually some degree of functional vision with a spectacle correction post transplant. This represents a major gain compared to advanced KC when there is most often no improvement at all, giving rise to a very high dependency on contact lenses. Therefore alternating between the best vision with contact lens wear and a less good but adequate result with spectacles post transplant may be a quite satisfactory way forward. There are also post transplant refractive surgical procedures which can be carried out to reduce astigmatism or high refractive errors which are contra-indicated for the pre-transplant KC eye.

Then the clinician’s perception of success may be quite the same as the recipient’s. There was a time, not that long ago, when if the graft was clear, it was successful and if it was not clear, it was unsuccessful. Nice and simple. There may have been 25.00 dioptres of astigmatism, or the eye was not used post op for some other reason, but that did not seem to be an issue. These days, everyone is more receptive to the patient’s input. However, use of the term ‘ survival ‘ is still more appropriate preferable.

Going for transplant… When?

Reverting back to the original title… When?

You can’t go back

No apologies for reiterating that the probability of keratoconus indicated transplant survival far exceeds that for failure. However, the surgeon cannot ‘unoperate’: an obvious comment but a necessary one. You cannot turn the clock back and try harder with contact lenses. You have to make the best of the outcome, and no surgeon can give a guarantee. All contact wearers live with the problems, but it is just not possible to visualise after the post-surgical situation. As the saying goes, ….The devil you know …. So the decision to proceed must be on the basis that you are sure your contact lens practitioner has done all he/she can do, and you have done all you can do, but the result is still not up to what you need.

The total rehabilitation can be 18 months: that is when you would expect to see a stable visual result. Before that, it is not correct to say you would be out of action, but the optical result may well fluctuate for that period. There may also be quite large changes after the sutures are removed: these may be for the better or worse from an optical standpoint. For very advanced KC, especially if it had reached the stage when contact lens management had ceased to be adequately functional, in many cases the vision can be better very soon after the surgery, especially comparing pre-op and post op unaided vision.

Timing

Then there is the crucial question of timing. A transplant is a major undertaking and a ‘season ticket’ for the clinic is required every bit as much pre-op. Perhaps more if anything. It is important to make appropriate provision for this.

Is there a benefit in early intervention?

Or, put the other way, is there a detriment in delaying surgery? There were some strong views expressed in the past that it was bad management bordering on malpractice to delay surgery because it became a technically more difficult procedure for more advanced cases. I put this question to the current surgeons from time to time and find few express the same very forthright opinion. If anything, the prevailing view is that there is not a case for pre-emptive intervention.

However, many transplant procedures now are deep lamella keratoplasty (DALK) rather than penetrating keratoplasty (PK). Either may be the preferred method. PK is a less complex procedure, and sometimes gives better vision. If a DALK is possible, one cause of rejection, that is due to the back layer of corneal cells, the endothelium, is significantly reduced. It could be that a DALK is more difficult to perform on a more advanced KC, or may be excluded if the eye has suffered a hydrops. If so, you could say that there is a case for pre-emptive action to prevent a hydrops. I remain unconvinced about that, especially as the resolved hydrops itself is not infrequently a considerable improvement on the pre-hydrops, even if it is a most unpleasant time during the acute phase. I am inclined to leave this discussion in this indeterminate state as it has more surgical implications than a long or short term management issues.

The fellow eye

Bilateral simultaneous surgery is not an option, so the decision ‘which eye’ is often a pertinent one. Generally, the more advanced eye would be the one to chose, but there may be some occasions when this is not so, perhaps, for example, if the worse eye has some incidental progressive pathology.

In many ways, when to transplant is as much to do with the state of the eye not under consideration for surgery. There are issues of loss of binocular vision, depth of visual field, a general feeling of poor balance, the distorted ‘rogue’ image impinging on the good eye, and probably others. But if one eye is seeing 6/6 (20/20 if you are from the US, 1.0 in Europe), you are very much in the land of the sighted however poor is the vision in the fellow eye. It has been demonstrated that some people judge the subjective result of a transplant on the basis of which is the better eye after surgery as much as on the improvement in the transplanted eye. I don’t think this is necessarily a reason for not carrying out a transplant in unilateral cases when the fellow eye is still good, but it certainly is a valid discussion point.

There is another debate with regard to the fellow eye. If the more advanced eye has reached the stage when appropriate to consider a transplant, it is argued that surgery should be expedited on the basis that the less advanced eye is going to follow the same progression pattern as the more advanced eye. If so, you could end up with both eyes having unsatisfactory vision at the same time. This is not without some validity, but my personal view would be to say there should be other more pressing reasons for proceeding. It depends on being able to predict progression, and the fellow eye does not by any means always follow the same pattern as the more advanced eye: some people are effectively unilaterally KC and remain so for many years.

Summary

So there it is, some of the issues of transplantation from a contact lens practitioner’s viewpoint. I am never going to perform a corneal transplant, but I do have some involvement before and after in KC contact lens clinics. The potential for a good final result with keratoconus indicated transplants is indisputably good, but I see it as a difficult decision while there is still a functional result with contact lenses. There are other details not covered, and of course there is another perspective more from the surgical standpoint. Condensed into one sentence, go for the transplant option, with optimism, when you need more than is available from contact lenses, when you have listened to and understood all the pros and cons, when you feel relaxed about it, and when you think the time is right.