Working in the workplace adjustment space, we see this quite often. An employee requests an adjustment to remove a barrier, and instead of a constructive conversation, the request is blocked. The justification usually sounds familiar: “It’s not reasonable,” or “If we do it for you, we’ll have to do it for everyone.” But too often, what’s really happening isn’t about reasonableness at all — it’s about control. Line managers, HR teams, and senior leaders act as gatekeepers, making subjective calls on what counts as ‘reasonable.’ And yet, under the Equality Act, it isn’t ultimately their decision to define what’s reasonable — it’s the courts’.

This article explores two essential but often overlooked aspects of workplace adjustments: the gatekeeping behaviours that can turn adjustments into a power struggle, and the subjectivity trap of defining what “reasonable” really means. Along the way, we will consider examples from sensory loss — particularly visual impairment, tinnitus and hearing loss — to highlight how seemingly simple requests are frequently blocked, and why workplace assessments are a practical, objective way to resolve disputes and remove barriers.

The gatekeeper problem

Many disabled employees describe the process of requesting adjustments as daunting and exhausting. Rather than feeling supported, they feel they must convince a panel of sceptics. In too many cases, the people deciding — often line managers or HR staff — are not experts in disability or workplace barriers. Instead, they rely on personal judgement, assumptions, or organisational culture.

The result is gatekeeping. Adjustments are seen not as legal rights but as optional benefits that must be justified, rationed, or resisted. Phrases like “if we let you, everyone will want it” or “we’ve never done that before” become shields against change. While often presented as protecting fairness, the reality is these decisions can be about maintaining control, avoiding change, or simply not wanting to engage with the complexity of disability.

When control outweighs inclusion

In practice, this gatekeeping can feel like a power trip. An employee discloses their condition, explains the barrier they face, and requests a change, and instead of collaboration, they are met with suspicion or resistance. For example:

- A member of staff with tinnitus asks to work from home two days a week to avoid a noisy open-plan office. The request is refused because “it wouldn’t be fair to the rest of the team.”

- An employee with visual impairment asks for screen magnification software. The manager says, “It’s too expensive,” without checking the actual cost (often less than £100).

- A worker with hearing loss requests captioning software for online meetings, but HR claims “we don’t support that platform.”

In each case, the employee is left feeling dismissed, while the manager maintains their authority. The adjustment itself may have been low-cost, simple, and entirely reasonable. But the refusal becomes a statement of power: “I decide what you get.”

What the law says

The Equality Act 2010 is clear: employers have a duty to make reasonable adjustments where a disabled worker would otherwise be placed at a substantial disadvantage compared to non-disabled colleagues. These adjustments are not perks or privileges; they are legal entitlements.

The Act deliberately uses the term “reasonable” to allow flexibility across different organisations and circumstances. What is reasonable for a small employer may differ from what is reasonable for a multinational corporation. Factors include cost, practicality, and the effectiveness of the adjustment in removing disadvantage.

However, the law also makes it clear that it is not the line manager’s subjective opinion that decides reasonableness. If challenged, it is ultimately for an Employment Tribunal or court to determine whether an employer has complied with their duty. Too often, employers act as though they alone define what is reasonable, forgetting that their decisions can and will be scrutinised externally.

The subjectivity trap

The word “reasonable” is deceptively simple. In reality, it is one of the most contested aspects of workplace adjustments. Employers often hide behind this term, claiming that a request is “not reasonable” without providing evidence or exploring alternatives.

For example, some organisations still argue that home working is not reasonable, even when the pandemic proved otherwise. Others dismiss requests for specialist software or equipment as too costly without researching prices or considering funding support. Subjectivity leads to inconsistency: one employee might receive adjustments easily, while another in the same organisation is denied.

Tribunals repeatedly show how subjective employer decisions can be overturned. Recent cases have found that denying home working for employees with health conditions amounted to a failure to make reasonable adjustments. These rulings highlight the risk of leaving such decisions solely in the hands of internal gatekeepers.

Why blocking adjustments backfires

Blocking reasonable adjustments has significant consequences:

- Legal risk: Employees can and do challenge refusals at tribunal, with employers facing damages, costs, and reputational harm.

- Business impact: Skilled employees leave organisations that do not support them, leading to recruitment costs and loss of talent.

- Workplace culture: Staff lose trust in leaders who dismiss or belittle adjustments, creating a culture of fear and disengagement.

Perhaps most importantly, blocking adjustments undermines inclusion. It tells disabled staff that their needs are secondary, their barriers unimportant, and their contributions undervalued.

Examples from sensory loss

Sensory loss provides clear illustrations of how adjustments can be misjudged:

- Tinnitus: Dismissed as “just ringing in the ears,” yet it can severely affect concentration, sleep, and mental health. Reasonable adjustments may include quiet workspaces, home working, or sound-masking devices.

- Hearing loss: In noisy offices, communication becomes exhausting. Adjustments such as captioning software, hearing loops, or quiet rooms can transform accessibility.

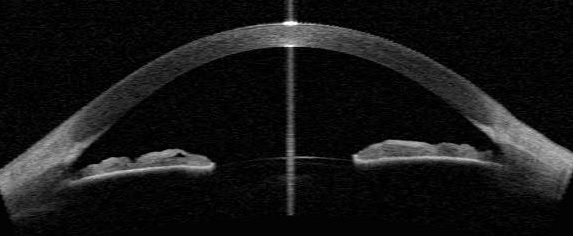

- Visual impairment: Lighting, screen glare, and inaccessible technology create daily barriers. Adjustments include magnification software, screen readers, lighting control, and accessible documents.

In all these cases, adjustments are often low-cost and practical. The real barrier is not financial but attitudinal — the reluctance of gatekeepers to act.

The role of workplace assessments

One of the most effective ways to avoid disputes and ensure compliance is through workplace assessments. These assessments provide an independent, expert view of what adjustments are appropriate. Rather than relying on subjective judgement, employers receive a clear report outlining barriers, solutions, and costs.

At Visualise Training and Consultancy, we carry out workplace assessments for people with visual impairment, hearing loss, and tinnitus every week. What we see, time and again, is that minor, simple adjustments make a huge difference — and prevent disputes before they arise. Assessments bring objectivity to a process that is too often clouded by subjectivity and power dynamics.

From gatekeepers to enablers

The fundamental shift required is cultural. Employers must move away from seeing adjustments as optional benefits controlled by gatekeepers, and towards recognising them as rights that enable inclusion. HR professionals and line managers should position themselves as enablers, working collaboratively with employees to remove barriers to success.

This means listening without judgement, seeking expert advice, and being open to change. It also means recognising that adjustments are not about giving someone an advantage, but about levelling the playing field. Fairness is not sameness — it is equity.

Conclusion

Reasonable adjustments are too often blocked by gatekeepers who see themselves as the final arbiters of what is reasonable. In reality, this power trip undermines inclusion, creates legal risk, and drives talent away. The subjectivity of “reasonable” makes it all the more important to approach adjustments with openness, evidence, and expert guidance.

Employers do not have the last word on what is reasonable — the law does. By embracing workplace assessments, listening to employees, and shifting from gatekeepers to enablers, organisations can create environments where disabled staff are supported, barriers are removed, and talent can thrive.

The question is not whether adjustments are reasonable, but whether employers are willing to step beyond subjectivity and power dynamics to build truly inclusive workplaces.

To find out more about making your organisation more accessible and inclusive for colleagues with hearing or sight loss, visit https://visualisetrainingandconsultancy.com/workplace-assessments/